A Technical Guide to Bayesian Optimization

In my previous posts, I introduced Bayesian Optimization and showed it working on a real coating formulation problem. The results were pretty good. We almost always found the best conditions with far fewer experiments.

But I didn’t really explain how it works under the hood. What’s actually happening when the algorithm selects the next experiment? Why does it find optimal conditions so reliably? This article digs into those questions.

The Three Key Components

Here are the three pieces that make Bayesian Optimization work:

1. The objective function The objective function represents the real-world process you are testing. It is the relationship between your inputs (temperature, dosage) and your output (hardness). In math, it’s the formula we want to solve; in the lab, it’s the physical experiment itself.

Important note: The objective function is the function you evaluate, not the goal itself. The goal might be to maximize (or minimize) the objective function.

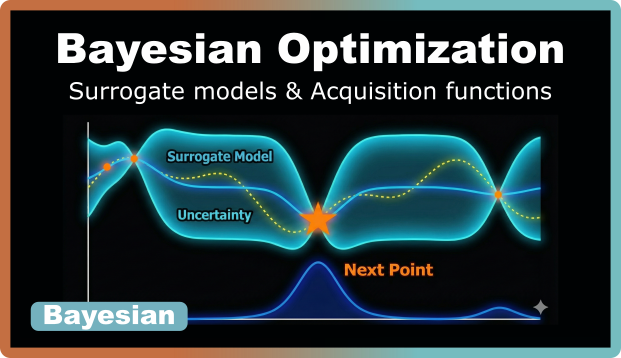

2. The surrogate model is a statistical approximation of your objective function. It’s the algorithm’s best guess about how your process behaves, built from the experiments you’ve already run. It predicts both what will happen at untested conditions and, importantly, provides an estimate of how uncertain those predictions are.

3. The acquisition function is the decision-making engine. It looks at the surrogate model’s predictions and decides which experiment to run next. Different acquisition functions have different strategies. Some focus on exploring the design space more, others on exploiting the most promising regions. You can choose between different acquisition functions based on your preferences.

TL;DR: The objective function is what you’re trying to optimize (the real, measurable outcome). The surrogate model is your mathematical approximation of the objective function. The acquisition function is the strategy that picks what to test next.

The Bayesian Optimization Cycle: A Closer Look

The basic cycle is straightforward: start with initial data, build a model, select the next experiment, run it, update, and repeat. While I introduced this in my first post on Bayesian Optimization Understanding Bayesian Optimization, let’s look closer at the mechanics of how the algorithm actually “thinks” during each step.

-

Starting with initial data: Bayesian Optimization can start with surprisingly little, often just 5 to 10 well-chosen experiments. Using a fractional factorial design or a Latin Hypercube Sample ensures you have a representative “skeleton” of the design space before the algorithm takes over.

-

Building the surrogate model: From these initial experiments, the algorithm builds the initial surrogate model. The surrogate model provides you with predictions as well as an uncertainty estimate for your whole design space. At every point, it says “I think the result will be around X, but it could also be so much higher or lower.” It is refined and improved with every new experiment you run.

-

Applying the acquisition function: The acquisition function is the “bridge” between the surrogate model and the objective function. It mathematically scores every possible next experiment based on two questions: “How good do I expect this to be?” and “How much will I learn by testing it?” A point that looks very promising gets a high score. A point where the model is very uncertain also gets a high score, because testing it resolves that uncertainty. The algorithm picks whichever point maximizes this combined score.

Important!: The maximum of the acquisition function is NOT the maximum of your objective function or even of your surrogate model. It’s simply the point that looks most promising to explore next (the one where you’ll learn the most or improve the most, or both).

Surrogate Models

Surrogate just means a substitute. In Bayesian Optimization, it is a cheap substitute for the expensive objective function.

In theory, you can use any model that can provide both a prediction and an assessment of uncertainty. Two common surrogate models that are used in Bayesian Optimization are Gaussian Processes (GP) and Random Forests (RF).

Gaussian Processes for Continuous Variables

Standard GPs assume continuity, so they require complex modifications to handle categorical data (like ‘Catalyst A vs Catalyst B’). When your variables are continuous (e.g. temperature, pressure, concentration), a Gaussian Process is usually the most suitable choice.

Here’s how it works: Instead of fitting a single curve to your data, the GP considers many possible curves that could pass through your measured points. At locations where you have data, the curves are pulled toward your measurement. In a perfect world, uncertainty would drop to zero here. However, since real-world experiments have noise, the model retains a small amount of uncertainty at these points to account for experimental error.

Between and beyond your data points, the curves spread out. Some predict higher values, some lower. The model’s prediction is the average of all these curves, and the uncertainty comes from the variation between the curves.

Deep Dive: GPs assume that similar conditions give similar results. If you test a reaction at 40°C and get 75% yield, you’d expect 41°C to give something close to 75% too. This assumption is why GPs work well for continuous variables but struggle with categorical ones.

Gaussian Processes assume smoothness. Move the slider to see how predictions change continuously.

Loading...

Random Forests for Discrete, Categorical or Mixed Variables

Sometimes your factors aren’t continuous. Maybe you’re testing different catalysts, solvents or other categorical variables where “similarity” isn’t obvious. For these cases, Random Forests are often a more practical choice. They naturally handle ‘mixed’ design spaces containing both continuous variables (temperature) and categorical ones (solvent type) without needing complex math.

A Random Forest is an ensemble of many decision trees. A decision tree is a model that makes predictions by following a series of binary splits based on the input data, similar to a flowchart. Each tree in the forest is trained on a slightly different subset of your data and makes its own prediction. The forest then combines these results:

- For predictions, it averages all the tree outputs.

- For uncertainty, it evaluates the level of disagreement among the trees. If the trees yield similar results, the model is confident; if the predictions are widely different, the uncertainty is high. However, Random Forests tend to be less statistically precise about this uncertainty than Gaussian Processes and they tend to underestimate uncertainty (are overconfident).

Random Forests also handle mixed variable types well. They can work with continuous (temperature, concentrations) and discrete (catalyst type, hardener type) variables in the same model.

Random Forests use decision trees. Move the slider to see each tree's path light up.

Acquisition Functions: The Strategy Behind the Search

The acquisition function takes the output of the surrogate model and uses that to decide where to perform the next experiment. Depending on the type of acquisition function, it might favor different areas in the design space.

Let’s look at the most common acquisition functions:

Expected Improvement (EI)

Expected Improvement is the workhorse acquisition function of Bayesian Optimization. It doesn’t just ask “What’s the probability of improvement?” It also asks “How much improvement can I expect?”

The math captures both the chance of beating your current best result and the magnitude of that improvement. This naturally balances exploration and exploitation: if a point has high predicted value, EI favors it (exploitation). If a point has high uncertainty, there’s a chance it could be much better than expected, so EI gives it credit too (exploration).

In practice, EI encourages broad exploration early on when uncertainty is high everywhere. As the model learns which regions are promising, it shifts toward exploiting those regions while still checking uncertain areas that might hide something even better. After enough experiments, you’ve mapped the landscape well enough to reliably identify the optimum.

EI is the most commonly used acquisition function because it rarely gets stuck in local optima and encourages broad exploration early on.

Probability of Improvement (PI)

Probability of Improvement is simpler: it just picks the point most likely to beat your current best. The problem is that it doesn’t care if you improve by 0.1% or 10%. Any improvement counts the same. This can lead to cautious, incremental gains rather than bold exploration. PI is less commonly used because of this limitation.

Tip: Click the chart to experiment manually.

Loading visualization...

Upper Confidence Bound (UCB)

UCB take an “optimistic” approach. Instead of trusting just the average prediction, it adds a bonus for uncertainty. Essentially it asks “What if this region is much better than I think?” This forces the algorithm to explore more.

Rule of thumb: If you’re unsure which acquisition function to use, start with Expected Improvement. It’s the most balanced and reliable choice for most optimization problems.

Batch Optimization: Running Experiments in Parallel

In practice, running experiments one by one is often a luxury you can’t afford. The time required for a single experiment is often nearly the same as for a batch of four or eight, so we usually run them in parallel.

Standard Bayesian Optimization is inherently sequential, but batch acquisition functions let the algorithm suggest multiple experiments at once. The challenge is avoiding redundancy. If the model identifies a promising region, you don’t want all your experiments clustered there. Functions like q-Expected Improvement (qEI) solve this by finding a set of points that collectively offer the most value, ensuring the batch is diverse enough to maximize what you learn.

Good to know: In qEI, q denotes the batch size. It is the standard mathematical convention for representing q points evaluated simultaneously in parallel BO.

The problem with predefined search spaces

Just like DoE, you need to define your search boundaries upfront. If the true optimum lies outside that space, the algorithm won’t find it. In theory, you could expand the search space as you go, but that’s technically tricky. A more pragmatic approach is to monitor progress and stop early if things aren’t looking promising (for example, when fewer than 50% of remaining candidates show expected improvement of at least 0.5%).

Four things to remember

- The surrogate model is your cheap stand-in for expensive experiments. It predicts outcomes and tells you where it’s uncertain, which is just as important.

- Match the model to your data type. Use Gaussian Processes for smooth, continuous variables and Random Forests for discrete, categorical, or mixed search spaces.

- The acquisition function isn’t looking for the best result. It’s looking for the best next experiment. That might mean testing something promising, or it might mean resolving uncertainty in an unexplored region.

- Expected Improvement (EI) is the most common acquisition function used. It effectively balances exploration and exploitation, making it the most reliable starting point for most optimization problems.